Imagine if doctors could tailor cancer treatments for individual patients, training their immune system to recognise and precisely target their tumour cells without harming healthy tissue.

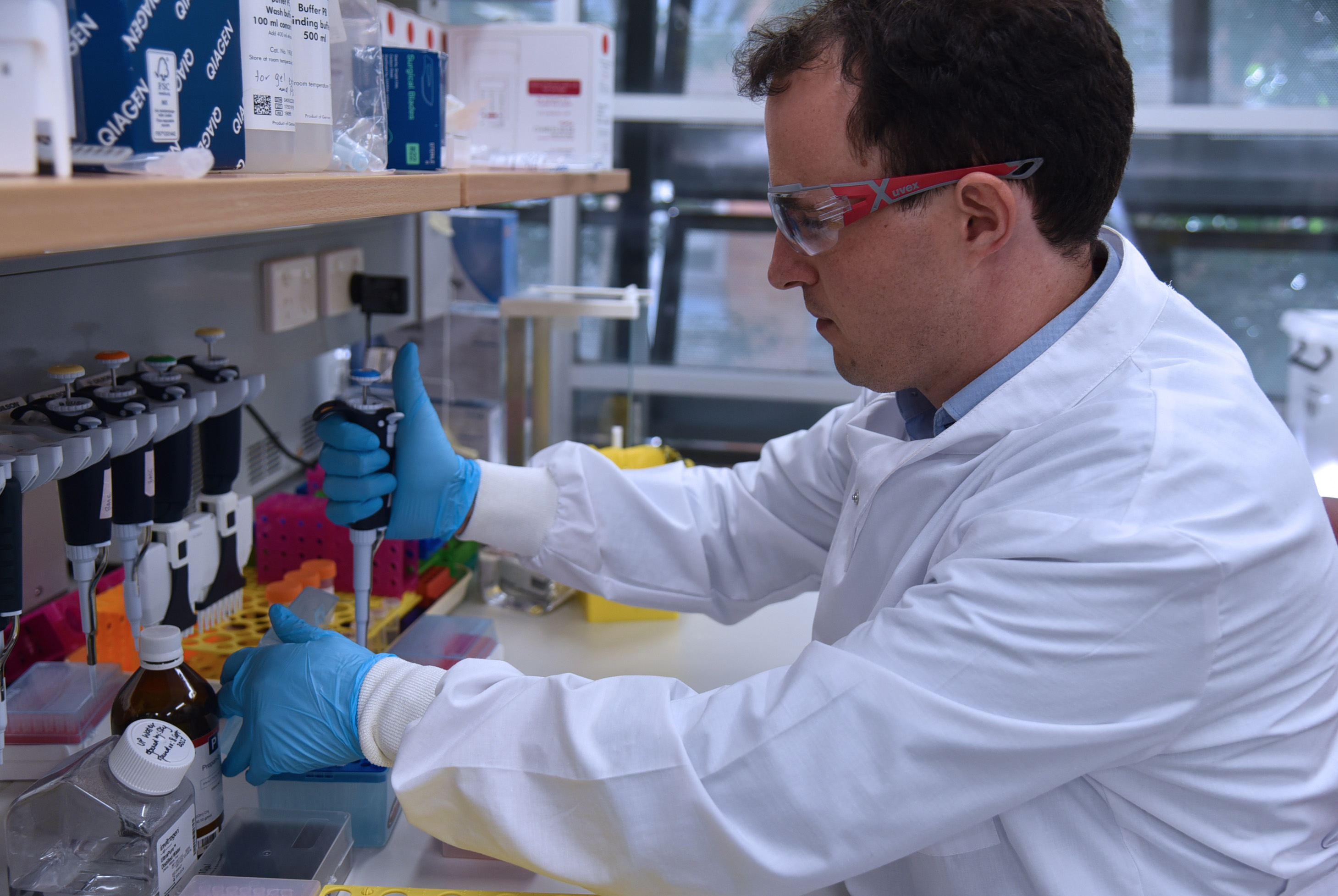

The University of Queensland is helping to make that a reality, bringing together the equipment and expertise to design, manufacture and deliver mRNA vaccines that match the specific treatment needs of each patient.

The new laboratory’s leader, Dr Seth Cheetham, said the use of personalised mRNA cancer vaccines could transform cancer treatment.

“Despite the huge potential, Australian researchers haven’t had the necessary infrastructure to build these vaccines, leading to a critical gap in the local drug development pipeline,” Dr Cheetham said.

“This lab changes that, with a leading team of investigators in a purpose-built space, working with local industry and academics to progress a range of high-quality vaccine candidates from design through to preclinical evaluation, with the aim of enabling future clinical trials.”

mRNA vaccines work by producing an immune response by using a copy of the mRNA molecule.

Dr Cheetham said early clinical trials were proving effective for patients undergoing treatment for a range of cancers, particularly melanoma and lung cancer.

“It’s known that the immune system can play an important function in combating these types of cancers,” Dr Cheetham said.

“But what's also really exciting is that early studies show that mRNA vaccines could be effective treatments for pancreatic cancer and even brain cancer, which are often harder to treat and have much lower survival rates.

“One of the reasons these cancers are harder to treat is because it’s difficult to engage the immune system to fight them off.”

Pancreatic cancer cells are known to create a cocoon of collagen fibres around the tumour that shield it from the body’s immune system and some treatments.

These fibres – similar to scar tissue – form when cancer cells produce enzymes that damage healthy tissue. The immune system and treatments such as chemotherapy are then unable to penetrate the barrier.

“The hope is that mRNA vaccines will be able to provoke the immune system to be able to better recognise cancer cells and evoke a response,” Dr Cheetham said.

Cancer is the world’s second leading cause of death, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths each year.

In Australia, more than 70% of people diagnosed with cancer survive 5 years after diagnosis. In some cancers – such as breast, prostate and melanoma – the survival rate is higher than 90%, thanks largely to early detection and treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation and surgery.

However, in many cases those systemic treatments that are also associated with many side effects.

“What we're talking about with mRNA vaccines is true personalised medicine,” Dr Cheetham said.

“We’re not trying to match the best drug to a patient, we’re actually manufacturing a drug for a single patient.”

The mRNA cancer vaccine hub began operating at The University of Queensland’s BASE facility in late 2024.

UQ’s BASE is already recognised as Australia’s leading provider of mRNA for research and pilot studies, and since its launch in 2021 has provided academic and industry partners with more than 300 experimental grade vaccines.

“As well as the potential impacts on patient health, mRNA cancer vaccines represent a $7 billion opportunity over the next decade,” Dr Cheetham said.

“This is a rapidly expanding industry encompassing researchers, biotech start-ups and multinational pharmaceuticals, and we will now be at the centre of a range of promising new treatment options.”

The new lab has received backing from Australia’s Medical Research Future Fund, global healthcare company Sanofi and the Queensland Government.

The 5-year program will also bring together partner investigators from UQ, QIMR Berghofer, Mater Research, Garvan Institute of Medical Research and the Queensland Children’s Hospital.

QIMR Berghofer Senior Scientist, Professor Rajiv Khanna AO, said designing and developing these vaccines will allow for rapid progression from pre-clinical testing to clinical trials.

“This process is often long and difficult if there is no local facility to help supercharge the research,” he said.

“It’s particularly exciting when you consider the cancers that are driven by viruses like HPV, as these cancers are very difficult to treat and are often detected at a late stage.

“Given there is now emphasis on developing new therapeutic targets via facilities like this, we can provide a much better outcome for people suffering from these conditions.”